The Art and Science of Traditional Soap-Making

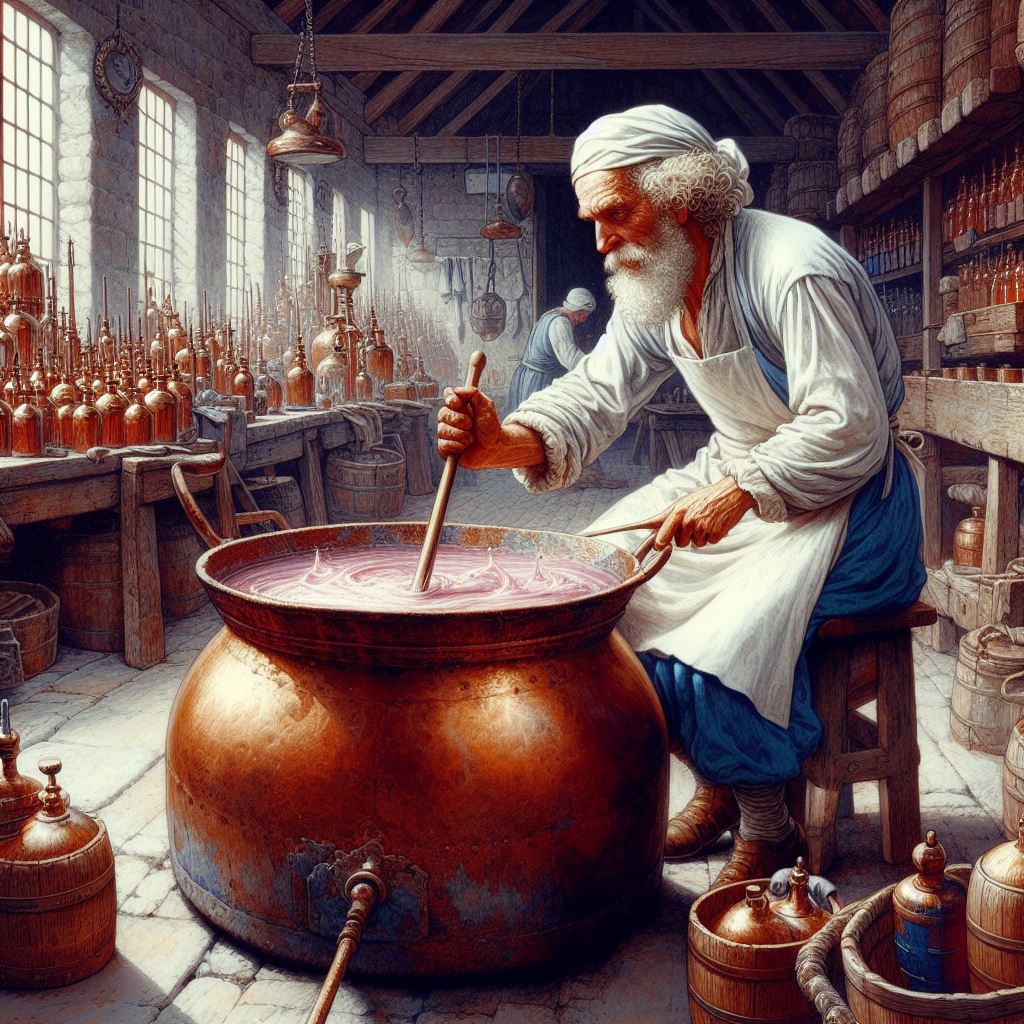

The Art and Science of Traditional Soap-Making From Tallow to Treasure: Mastering Saponification in the Craft of Soap-Making Soap-making in the 18th century relied on empirical knowledge and resource availability, with chemical processes like saponification shaped by practical experimentation. Below is a detailed analysis of the key steps and challenges, particularly regarding beef tallow’s interaction with sodium hydroxide (NaOH) Saponification Process Heating and Mixing (Fat and Lye) Animal fats like beef tallow (composed of triglycerides: glycerol + three fatty acids) were heated with lye (often wood-ash-derived potassium hydroxide or sodium hydroxide). The reaction split triglycerides into glycerol and fatty acid salts (soap): Triglyceride+3NaOH→Glycerol+3Sodium Fatty Acid Soaps. This process, though not fully understood chemically at the time, was optimized through trial and error Challenges with Concentrated NaOH and Beef Tallow Charring: High NaOH concentrations caused excessive heat, leading to fat decomposition rather than saponification. Insoluble Salts: Concentrated lye produced poorly soluble sodium salts, creating a barrier that hindered further reactions. Diffusion Issues: High surface tension in strong lye reduced NaOH’s ability to penetrate tallow, while early soap formation created a protective layer around unreacted fat. Equilibrium Shift: Excess NaOH shifted the reaction equilibrium backward, reducing efficiency. Empirical Solutions Soapmakers found weaker lyes (e.g., potassium-rich wood ash lye or sodium carbonate) more effective: Slower Reaction: Allowed better control and reduced side reactions like charring12. Homogeneous Mixing: Improved contact between lye and fat, ensuring consistent saponification. Post-Saponification Techniques Salting Out: Salt (NaCl) was added to separate soap from glycerol and water, causing the soap to coagulate into a solid mass. Marbling: Natural pigments or iron vitriol were occasionally used for decoration, though this practice was less documented in period sources1. Baumé Scale: Lye strength was tested using density measurements (e.g., floating eggs or potatoes) rather than standardized scales. Using the recipes from well-known companies, soda soaps can be superb, with a wonderful smell, nice lather, and a soft feeling on the skin. However, making such soap requires time, love, and lots of practice. Soap making is a difficult process and was not easy even 220 years ago. The effort put into making the soap is well worth it. Conclusion Conclusio The interplay of fat composition, lye strength, and temperature defined 18th-century soap-making. While concentrated NaOH posed challenges for tallow, weaker alkalis like wood ash lye or soda enabled controlled saponification. These methods laid the groundwork for modern soap chemistry and remain relevant for crafting traditional or artisanal products.

Lye Calculation: Experience in Soapmaking

Lye Calculation: Experience in Soapmaking Practical Approaches to Lye Measurement Soapmaking was once a craft passed down from generation to generation. Many soapmakers relied on traditional recipes and their own experience to determine the correct amount of lye. They knew the general ratios between fats (e.g., animal fat, olive oil) and lye (e.g., potash or caustic soda). However, calculating the exact proportions of ingredients was very challenging. There were several reasons for this. The Importance of Experience: Tradition Over Science Before modern chemistry, soap makers primarily relied on experience and tradition. Over generations, techniques and “rules” were passed down, based on trial and error. These rules were not scientifically precise, but they were sufficient to create usable soap. In the earlier centuries, chemistry was not as advanced as it is today. The exact way in which fats and lye react (saponification) was known, but there was a lack of a clear, detailed scientific understanding of chemical reactions and specific ingredient ratios. Absence of Stoichiometry Theory The theoretical foundation for the precise calculation of chemical reactions—known as stoichiometry—had not yet been developed. There were no established principles that would have allowed the creation of exact formulas for soap making. Instead, rough estimates were made. Lack of Precise Weight Measurement Tools There were no modern instruments for precisely measuring chemical substances (such as titration devices or modern scales). Simple scales were used, which only allowed rough measurements, and volumetric measurements (e.g., using bottles or cups) were also not always accurate. No Precise Temperature Measurements Temperature played a role in saponification (e.g., in maintaining the right reaction temperature), but precise thermometers were either unavailable or expensive and inaccurate. The lack of precise temperature control meant that the saponification process depended on experience and estimates rather than exact calculations. Inadequate Methods for Analyzing Raw Materials The exact composition of fats and lye could not be reliably measured. Chemical analysis of raw materials (fats, lye, water) was inaccurate, making it difficult to calculate the exact amount of lye required to completely saponify a specific amount of fat. No Reliable Measurement of Lye Excess In traditional soapmaking, it was difficult to measure the excess lye. An excess of lye could lead to a harsh, unpleasantly alkaline soap that could harm the skin, but this could not be easily quantified without specialized methods like pH measurement or titration. Lack of Control Methods Soapmaking relied heavily on the “feel” of the soapmaker. Many processes, such as determining whether enough lye had been added to completely saponify the fat, depended on visual and tactile cues that were not exactly measurable. The soapmakers not only had problems with the accuracy of the tools used, but also with the purity of the materials available. Fluctuating Fat Compositions Different fats (such as olive oil, beef tallow, or lard) have varying chemical compositions. This meant that the fat content and the types of fatty acids in each batch could differ. Without precise methods for determining the exact proportion of unsaturated or saturated fatty acids, it was impossible to make exact calculations. Different Lye Qualities Lye was often made from plant ash (e.g., oak wood or seaweed). The concentration of alkalis (potassium or sodium carbonate) in the ash could vary greatly. To test the quality of the lye, soapmakers would float it in water: the more lye was required, the heavier the solution was, and it would sink slowly. Variations in Soapmaking Soapmaking could vary greatly depending on the type of soap being produced. For example, adding different oils, herbs, or other ingredients would yield different results. The desired consistency and hardness of the soap also played a role and could be adjusted by varying the amounts of lye and fat. The Young Ladies’ Journal, 1896 Although they had to work with imprecise testing methods, varying quality of materials and sometimes only orally handed down secret recipes, these soap makers produced great soaps. Normal soaps for the commoner, cleaning soaps, cheap soaps for the poor and toilet soaps for the elite of society. The methods of the soap makers Use of Lye and Fat Tables As early as the 18th century, attempts were made to create tables for soap production. These tables indicated how much lye was needed for a specific amount of fat. However, these tables were often based on empirical data, as chemical analysis was not very accurate at the time. Potash (potassium carbonate), which was commonly used, could have varying concentrations. Simple Alkalimetry Tests Although modern alkalimetry was developed only in the 19th century, soapmakers knew simple tests to check the strength of lye. For example, they would drop the lye onto their skin to estimate its strength (a risky and inaccurate method). Or they used organic pH indicators like litmus or red cabbage juice to roughly determine the pH. Such tests helped assess the quality of the lye, especially since potash, made from burning plant ashes, was often uneven in strength. Empirical Control During the Process Soapmakers observed the chemical reaction during the process (called saponification). They checked the consistency and behavior of the mixture. For example, if a layer of fat formed, it indicated that the lye was insufficient. Before the advancement of modern chemistry, soapmaking was deeply rooted in experience and tradition. Techniques were passed down over generations, relying on trial and error rather than scientific precision. In earlier centuries, the lack of stoichiometric theory and precise measurement tools meant that soapmakers worked with rough estimates and empirical methods. Raw materials, such as fats and lye, varied significantly in composition and quality, making exact calculations nearly impossible. Instead, soapmakers relied on practical knowledge and observational skills to control the saponification process. Tools for measuring temperature, lye strength, and ingredient ratios were either unavailable or highly imprecise, leading to inconsistent outcomes. Despite these challenges, the intuitive methods and adjustments made by skilled soapmakers highlight the critical role of experience. Their ability to adapt to variations and rely on tactile, visual, and empirical tests ensured the production

Toxic Soaps

Dangerous Past Soap Ingredients and Why They’re Banned Ever wondered what went into soap centuries ago? From toxic minerals to questionable animal-based extracts, historical soap recipes were filled with substances we wouldn’t dare touch today. Dive into the fascinating—and sometimes horrifying—world of old soap-making ingredients that are now strictly off-limits. Animal-Based Ingredients: Cruel and Controversial Throughout history, animals were often at the heart of soap-making. Whether through exotic scents like musk and civet or fats sourced from slaughterhouses, these ingredients played a key role in creating lather and fragrance. Today, ethical concerns and environmental awareness have rendered these substances obsolete. Natural Musk: Extracted from the scent glands of male musk deer, musk was a prized ingredient for luxurious soaps. However, the process of obtaining musk often resulted in the death of these animals, driving them to near extinction in some areas. Today, synthetic musk provides a cruelty-free alternative. Civet: Derived from the perineal glands of civet cats, this musky scent was once used in high-end soaps and perfumes. The inhumane conditions under which civets were kept led to widespread criticism, and the ingredient has been replaced by synthetic or plant-based substitutes. Animal Fats: Fats from slaughtered animals, such as tallow and lard, were common in soap-making. While not inherently toxic, the reliance on industrial slaughterhouses raises ethical concerns. Many modern soaps now use plant-based oils, such as coconut or olive oil, as sustainable alternatives. Eichenmoos (Oakmoss): A lichen-derived ingredient with a woody, earthy scent, oakmoss was popular in historical fragrances. However, its potential to cause severe allergic reactions has limited its modern use. Mineral-Based Ingredients: A Toxic Touch of Color Minerals provided vivid pigments for historical soaps, but many came with a deadly cost. From arsenic-laden greens to cadmium yellows, these once-beloved colors are now synonymous with toxicity. Modern alternatives ensure vibrant hues without the health risks. Schweinfurter Grün (Paris Green): This vivid green pigment was made from copper and arsenic compounds. While it created stunningly colored soaps, its toxicity led to severe health problems, including poisoning from skin contact or inhalation. Auripigment and Realgar: These arsenic-based pigments produced brilliant yellows and reds but were highly toxic. Even handling these minerals could cause arsenic poisoning. Cadmium Colors: Bright yellows and reds were achieved using cadmium compounds. Cadmium is now known to be carcinogenic and highly toxic to the environment, making its use untenable. Neapelgelb (Naples Yellow): A lead-based pigment, it was once prized for its soft yellow tones. Lead poisoning risks have led to its complete ban in consumer products. Chemical Concoctions: Innovations Gone Wrong The rise of industrialization brought a wave of synthetic additives to soap-making. While some improved performance, others—like formaldehyde and phthalates—proved to be harmful to both people and the planet. These banned substances remind us of the fine line between innovation and safety. Formaldehyde: Used as a preservative in soaps, formaldehyde is now recognized as a carcinogen and a potent skin irritant. Its use is strictly regulated in modern cosmetics. Lilial (Butylphenyl Methylpropional): A synthetic fragrance ingredient once loved for its floral scent. It was banned in the EU in 2022 after being classified as toxic for reproduction. Diethylphthalate (DEP): Commonly used as a fixative for fragrances, DEP was later found to have hormone-disrupting effects. Public awareness and stricter regulations have largely phased it out. Ethanolamines (DEA, MEA, TEA): Used as pH stabilizers and foaming agents, these substances can react with other ingredients to form nitrosamines, which are carcinogenic. Salts and Acids: Corrosive and Harmful Borax: A common water softener and emulsifier, borax is now classified as a reproductive toxin and is banned in many countries for use in cosmetics. Chlorinated Lime: A mix of calcium hydroxide and calcium hypochlorite, this was used as a bleaching agent. It’s highly corrosive and poses serious risks to skin and eyes. Sodium Hypochlorite: Essentially liquid bleach, it was used in cleaning and whitening soaps but is highly irritating and unsafe for regular use. Sulfurous Acid: Used as a bleaching agent, it caused skin irritation and respiratory issues. Oxalic Acid: Historically used for bleaching, this acid is highly toxic if ingested and can cause skin burns on contact. Nitric Acid: Occasionally used in industrial soap-making, its highly corrosive nature made it too dangerous for continued use. Conclusion: The history of soap-making is a journey through trial, error, and, sometimes, danger. While early soap-makers sought to innovate, their reliance on harmful ingredients often came at a cost to health, safety, and ethics. Today, modern formulations prioritize both effectiveness and consumer well-being, ensuring that soap no longer poses hidden risks. By understanding the past, we can better appreciate the progress that has led to the safe, sustainable products we use today.

Ancient soap recipes

Unlocking the Secrets: Discover Vintage Soap Recipes Stay tuned as I unveil a treasure trove of soap recipes sourced from ancient books. Join me on this journey of rediscovery as we delve into the art of soap-making from generations past. Get ready to craft your own timeless creations! Honey Halfpalmsoap, Recipe from 1860 250 parts Lard 150 parts Palm oil 50 parts Coconut Oil 50 parts Colophony Die Darstellung der vorzüglichsten feinen Toilette – Seifen Substitute for Olive oil soap, Recipe I from 1867 30 parts olive oil 30 parts poppy seed oil or peanut oil 40 parts bovine fat Handbuch der chemischen Technologie, Band 6, Page 28 Substitute for Olive oil soap, Recipe II from 1867 30 parts olive oil 40 parts poppy seed oil or peanut oil 30 parts lard Handbuch der chemischen Technologie, Band 6, Page 28 Substitute for Olive oil soap, Recipe III from 1867 50 parts palm oil 30 parts sesame oil 20 parts bovine fat Handbuch der chemischen Technologie, Band 6, Page 28

Hot Process soaping – generations ago!

Hot Process soaping – generations ago! Explore the intricacies of soap production, from cooking to hardening. Learn precise methods for creating scum-free, pure soap bars of exceptional quality. This method is derived from a 300-year-old book for master soap makers. Step 1 – Cooking: Mastering the Initial Phase of Soap Production Cook all oils in 400 liter lye with 8-10° Baumé on low temperature, stir occasionally. As soon as it starts to simmer decrease the heat. Cook for a few hours. Add fresh 150 – 200 liter lye with 15-18° Baumé and stir for 15 minutes Cook for a few hours (days!) till the soap has an homogeneous apperance. Add 150 liter fresh lye with 15-18° Baumé. After cooking for another 2 hours the “Vorsieden” pre-cooking is done. Step 2 – Making Curd Soap: Refining the Soap Separation Process Remove the pot from the heat. Add a salt solution with 20 – 25° Baumé and stirr. When enough salt solution is added the soap seperates from the salt water. After 5 or 6 hours remove the 2/3 of the salt water. It should have 15 – 16° Baumé. Step 3 – Clear Boiling (“Klarsieden”): Achieving Clarity and Purity Add 600 – 700 liter lye with 25° Baumé. Turn on the heat. The soap expands and is very foamy. Stir it. Permanent stirring is important in this phase to decrease the cooking time. After 3 or 4 hours of slowly cooking increase the heat. This step should be ready after 8-10 hours resting. You will see little corns in lye. If you squezze the corns between the fingers thin and hard sheds should be formed. Let it rest for another few hours. Remove the soap from the now very concentrated lye. Step 4 – First Melting: Purifying the Soap through Melting Process The melting process takes place to remove excess lye, salt and impurities. Add 400 liters fresh lye with 8-10° Baumé. Increase the temperature and stir constantly. Stop stirring when all soap is melted. Cook 5 – 8 hours. To prevent clumping up add now and then pure water or lye with 2° Baumé. The soap must be separate from the lye during the whole time. Proof this with a glass [sic!] of the liquid. The soap swims on top of the lye. Let the soap rest for at least 8 hours. Step 5 – Second Melting: Final Refinement for Pure, High-Quality Soap Pour 150 liter of a soda/water solution (4,5-5° Baumé) in another pot, heat it till it almost cooks. Put the soap in this pot. Keep it warm for 4-5 hour and stirr occasionally. You know if the soap is ready when the impurities are visible again. Let the soap rest for 20 – 24 hours. The impurities are now in the weaker lye beneath the layer with soap. Remove the foam and save it for later. When you reached the pure soap remove it carefully and put it in a container. You will recognize the pure soap on the yellow-golden colour and the liquidity. Don’t forget to pour the soap through a fine plastic sieve. The now washed soap should have now a bright yellow colour, “does not have too much lye (is not “zapping”). Step 6 – Hardening: Achieving Uniformity and Stability in Soap Texture Now you have a container with soap. Stir it while it cools down to get plain and uniform soap. If all steps were done the soaps should yield: Soap Scum: 70-80 kg Pure soap: 1050-1080 kg Dirty and lyeheavy soap: 250-300 kg To get an excellent and beautiful toilet soap, bleach the palmoil. .

Carbonate Soaps

Carbonate Soaps A common misinformation about soda soaps debunked! Misinformation about soda soaps is common, especially in the USA. Some people believe that soap made with only fats and washing or baking soda produces a good soap. However, this is not true as soap making was a well-guarded secret and only specialists were able to make great soaps. They learned the exact procedures which took weeks, used different temperatures, different alkali substances, salts, additives, and more. They also did not have measuring tools like a pH meter but had methods to test the pH and quality without them. Challenges in Early Soap Making While simple saponifying of fatty acids is the first step of soda soap making, it does not produce a good soap. Using rancid fat, bones, skins, corpses, and other waste materials was common among older generations. These soaps were good enough to remove stains from clothes and strip fats from the skin but were not suitable for hands, bodies, or even the face. In Europe, people did not have the idea to use self-made soaps for the skin, and most German and Austrian families bought their body soaps instead of making them. Innovation and Controversy in Soap Making The knowledge of soap making was lost over time and oceans, and even in WW2, Germans and Austrians could buy fine body soaps and curd soaps for cleaning. War soaps had zero superfat and glycerine but were not lye-heavy. In those days, clay was used to fill the soap and make it heavier, along with sodium silicate, talc, alumina, kaolin, and other materials. The use of these materials was considered cheating and sometimes even forbidden by law. Using the recipes from well-known companies, soda soaps can be superb, with a wonderful smell, nice lather, and a soft feeling on the skin. However, making such soap requires time, love, and lots of practice. Soap making is a difficult process and was not easy even 220 years ago. The effort put into making the soap is well worth it. Crafting Excellence: The Art and Challenge of Soda Soap Making Using the recipes from well-known companies, soda soaps can be superb, with a wonderful smell, nice lather, and a soft feeling on the skin. However, making such soap requires time, love, and lots of practice. Soap making is a difficult process and was not easy even 220 years ago. The effort put into making the soap is well worth it.